Why Do So Many Organisations Refer to Climate Justice as One of Their Core Objectives These Days?

There is an increasing recognition that climate change is fundamentally a question of justice. That regards the responsibility for the problem and the efforts to tackle it. Different vulnerabilities to the impacts of climate change are both a reflection of structural injustices as well as the increasing intensity of climate impacts, many of which lie beyond the capacity to adapt. Essentially, it is about ‘what is tolerable?’ and ‘what is not?’.

Gradually, it becomes unacceptable to work on climate issues from a purely technocratic or economic perspective without considering social equity and justice aspects. While some organisations and companies use the focus on climate justice as a ‘marketing pitch’, more and more seriously explore how to integrate it into their work.

Gradually, it becomes unacceptable to work on climate issues from a purely technocratic or economic perspective without considering social equity and justice aspects. While some organisations and companies use the focus on climate justice as a ‘marketing pitch’, more and more seriously explore how to integrate it into their work.

As a result, Oxfam Quebec and PlanAdapt have partnered to provide youth and women right’s organisations in Africa, Middle East and Latin America with more guidance on what this new mantra, i.e. climate justice, could mean for their work. Before presenting the guidance itself, let’s explore the underlying concepts and principles.

Climate Justice – What Do We Really Mean by It?

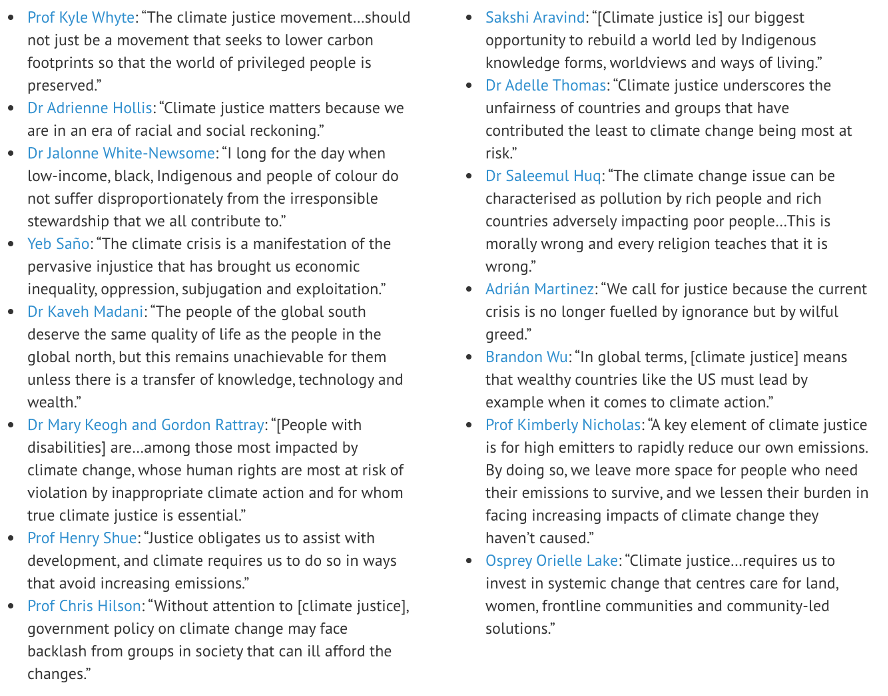

Climate justice is understood in a multitude of ways. However, the core of it touches upon the fact that the causes and effects of climate change, as well as efforts to tackle it, raise ethical, equity and rights issues.

Climate change is a problem that both reflects and perpetuates structural injustices. As such, climate change no longer appears only as an environmental problem requiring technological solutions and individual behaviour change, but as a problem with a strong ethical dimension: the solutions that are put in place must take into account the sharing of collateral damages and benefits.

Climate change is hitting hard, and it changes the way humankind thinks and acts in view of the future. What we need is a just transition to low-carbon economies and strengthened resilience capacities to adapt to the impacts of climate change. This can only be achieved if existing power structures are shifted and climate finance flows to where it is most needed, in areas and to population groups that carry the highest burden and that are most marginalised – among them women and youth. This is the core of climate justice. Climate justice sheds more light on the relationships between those who suffer most from the effects of climate change, and those who have contributed the most – through their GHG emissions – to the problem.

Climate Justice Looks at Injustice between Rich and Poor Countries and their Multi-Faceted Relations

By contrasting more “powerful” and more “vulnerable” actors and highlighting inequalities in terms of responsibility and in terms of capacity to absorb, adapt to and mitigate the climate crisis, it draws attention to the patriarchal, extractivist and neo-colonial economic and political system that has engendered this crisis. In addition, unequal power relations, lack of accountability and participation at national and sub-national scales are also issues that need to be addressed.

Climate justice is a useful concept to focus attention on the need to disrupt power relations and shift decision-making processes which lock in and reproduce climate injustices. It will hopefully help to bridge the gap between justice concerns in climate change funding and actual interventions on the ground. It is important to address structural root causes (historical injustices, land rights, gender inequalities, political participation and governance) to achieve climate justice goals in the long term.

The Mary Robinson Foundation (2020) states that climate justice “links human rights and development to achieve a human-centered approach, safeguarding the rights of the most vulnerable people and sharing the burdens and benefits of climate change and its impacts equitably and fairly”. In the end, there is no single way to define, let alone champion, climate justice. However, in combination with other current social justice movements (including environmental justice), there is a strong recognition that climate justice needs to be an additional component of the fight for more equality and justice.

Five Dimensions of Climate Justice

There are five different dimensions of climate justice, very much interlinked but focusing on discrete sub-aspects of justice (see also Burnham et al., 2013 (part 1; part 2); Manzo, 2021; Walker, 2012; Svarstad et al., 2011).

- Procedural justice – relating to who is at the decision-making table

- Distributional justice – relating to the distribution of responsibilities, capacities, costs and benefits of climate action

- Recognition justice – recognising and taking action to address structural constraints

- Corrective justice – providing remedies for past injustices

- Intergenerational justice – recognising the rights to pollute and leaving options that allow future generations to adapt

Procedural climate justice. This aspect of climate justice is fundamentally about decision-making processes, aiming for responses to climate change to be fair, accountable, and transparent. Core to this are issues of public participation, due process, and representative justice. This can include access to information, access to and meaningful participation in decision-making, lack of bias on the part of decision-makers, and access to legal procedures. Procedural justice generally focuses on identifying those who plan and make rules, laws, policies, and decisions, and those who are included and can have a say in such processes. It also focuses on seeking to unveil the (un)fairness of the processes through which decisions are made.

Distributional climate justice is essentially about the distribution of responsibilities and benefits arising from responses to climate change. This is frequently discussed in relation to ‘just transitions’ to a zero-carbon economy. These transition processes are often related to issues of social justice. This includes, for instance, strategies for defending the legal rights of existing land users from land grabs, and proper compensation for those whose land is acquired (for biofuel projects, for example). This prevents some of these injustices from occurring. New low-carbon or climate investments should consider existing social inequalities with a view to thinking about safeguards and governance innovations that might be required to ensure poorer groups do not pay the price for decarbonisation efforts. A similar risk is often associated with investment driven by the rules and regulations of carbon markets. Therefore, it is essential to bring a wider range of interests and voices into decision-making about these transitions.

Recognition justice is closely related to both procedural and distributional justice, but focuses in particular on the recognition of difference (Fraser, 2000). Recognition is defined here as an ideal mutual relation between groups, in which each sees the other as its equal. In practice, it means identifying people whose vulnerability may be worsened because of a process such as a low-carbon transition, for example. Recognition justice centers on unveiling those who may face intolerance and discrimination and supports the idea that they should be guaranteed a fair representation of their views without distortion or fears of reprisal (McCauley et al., 2013; Sovacool et al., 2019).

Corrective justice is a fundamental type of justice, concerned with the reversal of wrongs or the undoing of transactions. Also called climate change litigation and climate harm reversal, efforts should be made to focus on the corrective justice potential for those who face negative climate impacts such as displacement stemming from climate change.

Intergenerational justice is focused on elements of justice that most often surface in debates on environmental resources and sustainable development. Brundtland (1987) had defined the term intergenerational justice as the ability of current generations to meet their needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In climate justice struggles, justice for future generations is a central mobilising claim: holding the current generation of decision makers and polluters to account now for failing to act and imposing on future generations risks and dangers for which they are not responsible.

Some activist groups and scholars argue for linking different forms of climate justice to a framework for transformative climate justice (Newell et al. 2020, Mary Robinson Centre for Climate Justice).

But how do these abstract ideas relate to the reality of organisations in countries of the Global South? Read more about this in related blogs:

What Does Climate Justice Mean for Youth and Women Right’s Organisations in Africa, Middle East and Latin America? (Part 1) and What Does Climate Justice Mean for Youth and Women Right’s Organisations in Africa, Middle East and Latin America? (Part2)